Dear Clara:

The Story of a Shattered Family

Dear Clara

The Story of a Shattered Family

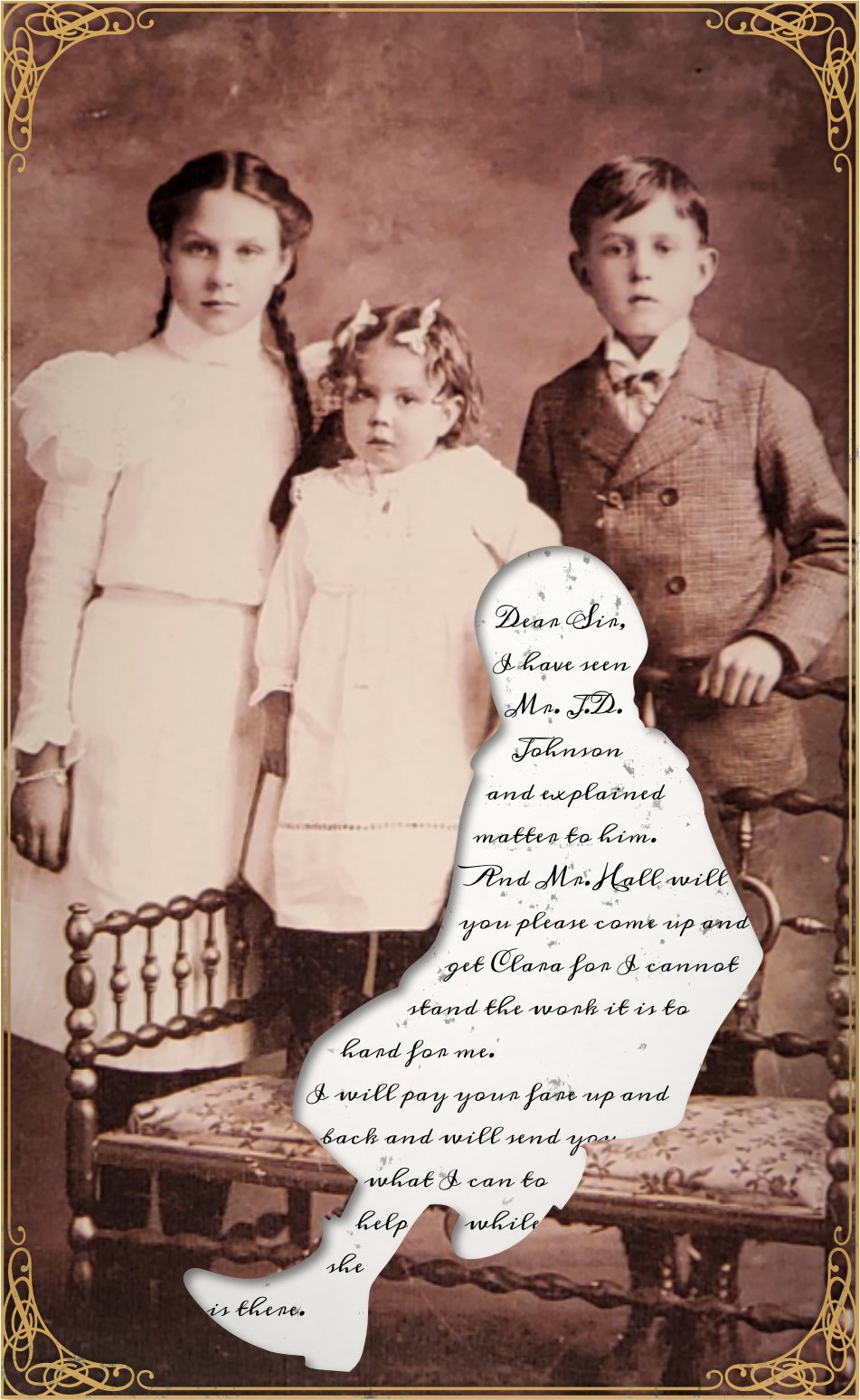

Dear Clara: The Story of a Shattered Family is the tale of an eleven-year-old girl’s traumatic adoption, a desperate mother’s remorse, and a younger sister’s efforts to reunite the people she loves.

Set in North Dakota in the early twentieth century, the novel focuses on Clara, sent away by her destitute family, and Lilly, left behind with her nightmares and fragmented memories.

Interspersed among the pages of their narratives is the decades-long correspondence between the dedicated director of the orphanage where Clara is taken, and her grieving mother Delores, who recovers from the Spanish flu and a mental breakdown, but who never stops worrying about her child’s welfare. The correspondence is a heart-breaking testament to the inadequacies of a society whose “orphans” were more often than not the abandoned children of the working poor. And where it was advised to “look ahead, not behind,” to deal with one’s trauma.

This story is based on the childhood of the author’s grandmother, revealed through two decades of actual letters preserved by the North Dakota Children’s Home Society. It is set in an era with some of the same issues – a global pandemic, the impact of medical and childcare bills on the economically fragile, women’s limited access to wealth – that challenge us today.

Excerpt

Clara and her sister Lilly learn they are going to be put into foster care.

From Dear Clara: The Story of a Shattered Family

Mama was talking, but Clara couldn’t understand the words. It was the morning after the breaking of the plates, and she sat on the edge of the bed and watched Mama pace the floor of the small room. She was trying to tell Clara something, but all Clara could do was stare at the leg she knew must be bandaged under her skirt. It was no doubt why she hobbled as she walked back and forth across the room. The determined set of her jaw reminded Clara of the way she’d looked when she’d insisted Albert come to Daddy’s funeral. Her eyes blazed.

“Clara. Do you understand what I’m telling you?”

She had heard the words, yes. But did she understand? The tornado throwing her life into bits, like splinters of a demolished house, made it hard to understand.

She was going into foster care.

Lilly would be in foster care as well, her mother said. She wanted her to know she wasn’t the only one being sent away. But no, Lilly wasn’t coming with her. There was no room for her where Clara was going, and the family that had agreed to take Lilly only had room for one small girl.

Her baby sister. Who would help her find Muffin when she was lost? Who would finish reading Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to her? And who, Clara wondered, would walk Lilly to school when it was time? They were supposed to do that together.

Clara could barely hear over the roar in her head. The words coming from her mother were sharp, and they lashed at Clara like shards of shattered glass.

Mama would always be her mother, she kept saying, but right now she couldn’t take care of them. Because she was a widow who now had to go to work at a store and couldn’t be home to cook their meals or watch over them. Jane could work. Albert would finish sixth grade then go to work full time as well. But Clara needed an education, her mother said. And Lilly needed care. They wouldn’t be far away, her mother assured. And it wasn’t an orphanage, just places to live where other people could watch over them and . . .

In Clara’s mind, plates began crashing and she heard a scream. Then she realized she was the one screaming. She jumped to her feet and found her balance. She kicked her mother hard, aiming for the tender wound beneath her dress. Then she was down the stairs almost too quickly to hear Mama sobbing her name.

Lilly was on the rug with Muffin and her new wooden blocks, and some of the boarders were sitting nearby, maybe reading, Clara wasn’t sure. All she saw was her baby sister, who looked up at the sounds from above.

“We have to go,” Clara said. “Now!” Lilly didn’t ask anything, just grabbed Muffin and followed her sister to the coats where they hung by the front door, and the girls were outside too quickly for anyone to stop them.

It was a day with sun but no warmth, and Clara didn’t know where to lead them but away. They left footprints in the snow, and she knew they’d be easy to follow should anyone want to. They held hands as they walked, and Clara found herself heading toward the church, mostly because they were there the day before and she didn’t know where else to go. If they were lucky, someone would be working in the office and they could at least go inside to get warm. She looked behind but no one was following yet, so she sped up and tried to find other footprints to mix with theirs. She vowed her mother wouldn’t find them. Ever.

“Where are we going?” Lilly finally asked. She was working hard to keep up. Clara wasn’t ready to explain, so she just answered, “The church.” As they neared, a small whiff of smoke appeared out of the stovepipe of the office. In spite of her confused feelings about the good reverend, Clara knew he would let them in to warm themselves. They’d left too quickly to put on gloves or winter boots, so for the moment that would be enough.

When she pushed the door open it was the reverend’s wife, Mrs. Whitehead, who was huddled over the desk.

“Girls, you surprised me,” she said, with her hand on her chest. Mrs. Whitehead recovered and gave them a polite smile. “Come in and get warm. Is your mother here?” She looked over their heads, but Clara closed the door behind them. Mrs. Whitehead drew them to the stove. She waited a moment for some kind of explanation, but both girls remained silent.

“What are you doing out on such a cold day?” she finally asked. In the glow of the stove her graying hair shone with coppery red, and her light eyes were wide with concern. The reverend and his wife had no children, and Clara had never met her own grandparents, so she always imagined Mrs. Whitehead to be what her missing grandmothers might have been. She wanted to trust her, to tell her what was happening, but when she started, she cried so that her breath caught in her throat.

“Let’s go to my house and get you something warm to eat. Then we’ll let your mother know where you are. She must be so worried.”

Clara found her voice. “We can’t go home, ma’am.”

Mrs. Whitehead looked at her curiously but didn’t argue.

“My house is just next door,” she said.

It was a big and rambling place, probably designed for a minister with a large family, and it was warm inside and full of upholstered furniture. She had them sit at a shiny table in the spacious dining room. “Take off your coats,” she said. “I’m getting you soup.” She went through a swinging door into the kitchen, where she spoke quietly to someone.

It was the reverend. He walked out to meet them wearing an apron and carrying a wooden spoon. They’d never seen him out of his minister collar before.

“Hello, girls. You’re here for soup.” It was a statement, not a question, though his eyes were full of them. Then he was back in the kitchen and in a few minutes returned carrying a tray with steaming bowls that he set on the table in front of them. “Eat.”

Clara realized she was hungry. She filled her spoon, blew across it, and watched the steam fly away. This soup had a smell and flavor that was familiar and reassuring. She couldn’t place it but happily accepted a second bowl.

“Thank you,” she said finally. Lilly hadn’t spoken at all, but she’d eaten her share. Both the Whiteheads were sitting across the table.

The reverend spoke. “I think it’s time to tell us what happened.” Clara looked at her little sister, who was watching her with large, sad eyes.

“She’s sending us away,” Clara said, and the tears started again. “Our mother is sending Lilly and me to foster care. And we won’t be together. And I hate her.”

She said it all at once and then had to pause to draw in a breath. Lilly looked as if she’d been hit, and tears fell silently down her cheeks.

“Your mother is in a difficult position,” said the reverend. “Since your father died, she has done her best to keep you all together. But it’s very hard, Clara. It’s a hard thing to do.”

She was suddenly back on the porch of her old home eavesdropping on a conversation that she only now understood.

“You must make this as easy as you can on your mother by cooperating. This is very hard for her, but she is doing what she thinks is best.” Clara saw that neither of the Whiteheads was surprised by this news. They’d likely aided Mama in coming up with this terrible plan. She’d come to the wrong place. They weren’t going to help.

She stood and took Lilly’s hand.

“Stay,” said Mrs. Whitehead. “Stay with us tonight. We have lots of room. You and Lilly. Take a day to become accustomed to this idea. It’s so hard, we know. But truly your mother doesn’t see any other way.”

More than anything, Clara didn’t want to go home. She looked at Lilly, who was wiping her nose with the back of her hand.

She answered for them both with a nod.

“I will go see your mother,” said the reverend.

When he was gone, Mrs. Whitehead fussed over them. “Would you girls like baths? I have some clean nightgowns from the charity bins I can give you. You must be exhausted.”

Some time later they were upstairs in a proper bed. They’d never slept on anything but an old cot. This was soft and high up off the floor. Clara felt a bit like a princess, then remembered the dress her mother had sewed for her once that had made her feel like a princess; her eyes watered again, but she was too tired to cry. They lay in the dark space warmed by the fireplace, with Clara’s arms around Lilly and Lilly’s arms around Muffin. Lilly had hardly spoken since they’d run out the front door.

“Will it be scary where we’re going?” she asked. Clara wondered if she understood they wouldn’t be together.

“No, I’m sure it won’t,” she lied. “I’m sure the people will be kind and maybe even get you another doll. And books. There could be lots of books.”

They were still for awhile, and Clara thought Lilly had gone to sleep, so when she spoke it startled her.

“It’s the soup,” she said. Clara’s mind was full of many things, and she’d forgotten there was something familiar about that soup. She had no idea what Lilly was talking about.

“What?”

“The soup,” she said softly. “It’s the ‘Miracle of the Soup’ soup.”

The Reverend Whitehead was the angel? Or his wife? Probably both. Their kindness had saved them. Now they were telling her to cooperate with their mother as she handed them off to strangers. Away from Lilly and everything she knew. She hated the Whiteheads. Just like she hated her mother.

There were no more angels for her to believe in.